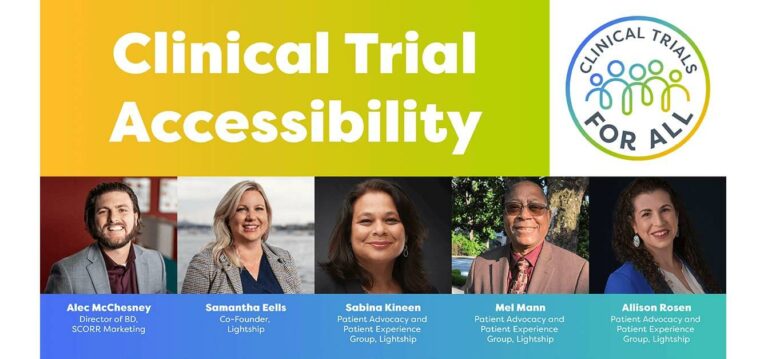

By: Meredith Boley, Bezyl For people struggling with their mental health, support can be life changing. The same is true for people who participate in clinical trials! The clinical trial environment, which can sometimes lack adequate psychological support and resources, often creates or compounds mental health struggles. As a result, both patients and caregivers may feel isolated, overwhelmed, and unsupported. Unpacking the Patient Experience Clinical research participants can experience heightened levels of stress, anxiety, uncertainty, and even depression. This is primarily due to the unfamiliarity of the trial process, potential side effects of treatments, concerns about their health outcomes, and because they are often managing a significant illness or condition while navigating trial complexities that their social circle may not fully understand. Caregivers Face Mental Health Challenges, Too Caregivers of clinical research participants can also face unique mental health challenges. They may experience high levels of stress and anxiety due to the demands of caregiving, concerns about their loved one’s health, and the emotional burden of supporting someone through a clinical trial. Caregivers may also experience feelings of isolation, fatigue, and burnout, especially if they lack a support network or resources to help them manage their caregiving responsibilities. Why It Matters Patient and caregiver mental health during clinical trials is important because it directly impacts both groups’ overall well-being, which can affect a patient’s ability to stick to the trial protocol and to manage treatment-related side effects. When mental health is compromised, patients may experience reduced motivation, increased fatigue, and a decline in physical health, impacting trial outcomes and data reliability. Furthermore, strong mental health support can enhance retention rates, reduce dropout rates, and help ensure the trial’s success. By addressing mental health proactively, both patients and caregivers are better equipped to handle the emotional and psychological demands of participating in a clinical trial, leading to more accurate and reliable study results – which ultimately deliver better treatment options to the people who need them. 14 Clinical Trial Mental Health Tips With this in mind, here are 14 ways that patients and caregivers can give their mental health a boost while navigating clinical research participation. Establish a Routine: Maintaining a consistent daily routine can provide a sense of normalcy and stability, which can help reduce anxiety and stress. This includes regular sleep, exercise, mealtimes, and scheduled relaxation or leisure activities. Stay Informed: Understanding the clinical trial process, potential side effects, and expectations can help reduce fear and anxiety. Patients should feel empowered to ask questions and seek clarification from their healthcare providers. Knowledge about the trial can help patients feel more in control of their situation. Access Professional Mental Health Support: Engaging with a therapist, counselor, or psychologist who specializes in working with clinical trial participants can provide tailored emotional support and coping strategies. Professional support is invaluable for managing anxiety, depression, or other mental health concerns that may arise. Practice Self-Care: Self-care activities, such as reading, journaling, meditating, or engaging in hobbies, can help manage stress and improve overall well-being. Taking time for oneself is crucial for maintaining mental and emotional balance during the demands of a clinical trial. Physical Activity and Exercise: Regular physical activity is proven to boost mood, reduce stress, and improve overall mental health. Even light exercise, such as walking, yoga, or stretching, can help alleviate anxiety and depression symptoms and improve physical health, which can be particularly beneficial during clinical trials. Nutrition and Hydration: Eating a balanced diet and staying hydrated can significantly impact mood and energy levels. Good nutrition supports brain health and overall well-being, which is important for maintaining a positive outlook and physical health during a clinical trial. Build a Support Network: Build a support network that includes healthcare providers, fellow trial participants, friends, family members, and community groups. This network can offer emotional support, practical advice, and a sense of solidarity. Set Realistic Goals and Expectations: Setting achievable personal goals can provide a sense of purpose and accomplishment. It’s also important for patients to set realistic expectations about what they can handle and to recognize their limits to avoid burnout or frustration. Practice Mindfulness and Relaxation Techniques: Techniques such as deep breathing, meditation, progressive muscle relaxation, and visualization can help reduce stress and anxiety, improve focus, and promote a sense of calm. These practices can be especially helpful for managing the emotional ups and downs that come with clinical trials. Keep a Journal: Writing down thoughts, feelings, and experiences can be therapeutic and help patients process their emotions. Journaling can also be a useful tool for tracking emotional states as well as identifying patterns and triggers of anxiety or stress. Engage in Positive Social Activities: Participating in social activities or connecting with friends and family can help reduce feelings of isolation and provide emotional support. Engaging in positive, supportive social interactions can improve mood and provide a sense of normalcy. Stay Connected with the Research Team: Maintaining open communication with the clinical trial research team can help address concerns or issues as they arise. Feeling supported and heard by the research team can alleviate stress and improve the overall trial experience. Create a Calming Environment: Having a designated, comfortable space for relaxation or mindfulness practice can help manage stress and provide a refuge during difficult times. This environment can include calming elements like soft lighting, soothing music, or aromatherapy. Connect with Support Communities: Connecting with others in similar situations can help reduce feelings of isolation and provide valuable peer support. Find Mental Health Support Tools That Work for YOU Creating a supportive environment on your own can be challenging, even with the above tips. That’s where support tools come in! Bezyl is an app that offers a personalized platform for mental health tools. Designed to support clinical trial participants and caregivers – as well as other people who’ve experienced trauma – the app includes features like: Mental well-being is crucial for navigating the challenges of a clinical trial, maintaining resilience, and improving overall outcomes. Don’t hesitate to seek support, whether through Bezyl, healthcare providers, or your personal network. More About Bezyl: Clinical Trials For All partner Bezyl was founded with a mission to revolutionize mental health support by leveraging the power of connection and community. Our vision is to create a world where mental health support is accessible, personalized, and integrated into everyday life. Our app, available on Google Play and the Apple Store, offers a comprehensive suite of tools designed to support mental well-being. From connecting with family and friends through our Spheres of Support feature to tracking moods and accessing a library of resources, Bezyl is here to help you every step of the way. Visit Bezyl.com.