My Journey With Cystic Fibrosis

Being born with cystic fibrosis (CF) — a progressive, genetic lung disease — I have had countless health care encounters throughout my life, spending time in the hospital being treated for lung infections through adolescence and into adulthood. From these experiences, I learned the power that lies in self-advocating for my health in the clinical setting.

I studied biology in college, and worked in a laboratory after graduation. It was in this role that I first realized my own experiences as a patient could help bridge the gap between research and patient communities. At the time, I was studying antibiotic resistance — something I have dealt with in my medical journey using antibiotics frequently to treat lung infections, which over time means that my body has developed a resistance to them. There have been points in my life where treatments weren’t effective because of this. This connection between my own health experiences and the research in the laboratory led to my passion for building inroads between research and patient communities.

Amplifying the Patient Voice in Research

I began lending my voice as a patient perspective in research, serving on various committees with the CF Foundation, on advisory boards, and in consultant roles with pharmaceutical and healthcare companies developing patient-facing lay language materials to support health literacy, reviewing clinical trial protocol designs, and overall helping industry to consider the patient experience throughout drug development.

I have grown my industry connections by speaking on panels, at conferences, and other events branching beyond CF consultation, ensuring the patient perspective is represented within research for other rare diseases. Now, I work with industry professionals to identify and meet the needs of many different patient communities.

Clinical Research and Phage Therapy

About the same time that I started my advocacy journey those years ago, I became very sick with a lung infection that was resistant to all antibiotics. I was fortunate enough to be connected with a company doing a documentary on phage therapy — an experimental treatment alternative to antibiotics. I quickly inquired if I could partake in this research. At the time this was experimental with no clinical trials available, and I was granted access through the FDA expanded access program.

Since the time of my treatment, which proved to be successful in treating my infection, there has been a lot of advancement in the field of phage therapy, with clinical trials now available and more research being explored.

I am a strong proponent of clinical trial participation. The best way to bring new treatments to communities is by participating in the necessary research. As a patient, it’s a commitment that needs to be decided carefully, but if you do choose to participate, you become a piece of the larger puzzle that leads to new medications, therapies, and even cures. Patients can and should be involved in the decision making process and outcomes of new treatments.

Unfortunately, I am not eligible for most CF clinical trials because my lung function is below 40%, one of the most common general exclusion criteria used in research. Because I believe all patients should have opportunities to participate in clinical research, I have advocated for the development of adaptive trial endpoints and protocol designs to make clinical research more inclusive to a broader population of patients. Everyone wants new treatments, but the eligibility criteria often exclude the patients who need new treatments the most.

With my personal health experiences in the care setting, my work with industry, and the value that I know exists in our voices as patients, my passion extends to empowering others to be active participants in their health care too, gaining knowledge about their disease and participating in clinical research.

The Importance of Trust and Connection Between Patients, Providers, and Industry

A large part of my advocacy at this point centers around making sure patients are heard, collaborated with, and brought into the conversation early on — from trial protocol development all the way to the post-study dissemination of information. This collaboration between the pharmaceutical industry and patients is vital, and equally important is the relationship built between patients and providers.

The doctor–patient relationship is arguably the most important in health care, as doctors are the most trusted source and a channel into the rest of the health care system. When patients don’t feel they can trust their providers, or don’t have a strong relationship with them, this impacts the way they perceive and interact with the health care system. Bad experiences with doctors can contribute to the overall opinion someone has of the health care system and lead to poorer health outcomes for people.

When negative interactions occur between a doctor and patient, patients are far less likely to trust their doctor’s options about their health regimen, leading to potentially less frequent checkups and worse health outcomes. Based on my experiences as a patient advocate in the clinical trial space, patients are also less likely to find out about and enroll in clinical trials due to less frequent follow up and reduced trust in doctor’s encouragement of participating.

Changing an already established bad relationship to a good one can be challenging, but there are ways to effectively communicate to try to keep patient–doctor relationships positive and supportive — or at least amicable. This includes viewing doctors as allies, not adversaries, and trying to build a connection of mutual respect.

Patients and doctors are both experts on health care in different ways. As patients we understand aspects about our condition that our doctor may not, and doctors may understand treatments, procedures, and methods of care better. Together, we can make the best decisions for our care, but it starts with voicing our thoughts and opinions and feeling comfortable to do so.

Knowing Our Value as Patients

In order to be involved in our own care and treatment, to decide whether to be involved in a clinical trial or not, and to make those decisions together with doctors, we must see ourselves as equal partners. Patients know the most about their body and their day-to-day symptoms and experiences. Voicing our thoughts and concerns about a treatment plan or trial opportunity is vital to our overall health, and doctors often appreciate input and collaboration.

If we don’t understand something — such as informed consent or what testing will be required within a trial — it’s important to insist that the doctor listen and explain tests, procedures, and new research. Be eager to understand and gain knowledge about health care. If someone has an interest in a new treatment or has heard about some new research or trial, it’s important to ask questions about it during appointments. As patients we may actually be sharing some new information with doctors who may not have known this information beforehand.

It is important to do our part as patients to take ownership of our health and do what we can to support the relationship we have with our care providers and to gain more understanding about clinical research and our care as a whole. This helps to create an environment where optimal health interactions exist and our health remains the number one priority in the care delivery setting.

Health Care’s Support of Patients

I view health care as a loop. As patients, we are one group that contributes to improving health care, but it can’t be done without the physicians, researchers, and industry organizations. They are our partners in advancing research and treatments.

Empathy must be the root of all health care interactions. For there to be meaningful communication between larger pharmaceutical companies and the patients they are serving, there needs to be a desire to understand the needs of patients and the barriers they may be facing in their daily lives. Real patient care happens along the way, when industry provides support and interest in patients outside of their experiences of just taking a new medication or being recruited for a trial. Our lived experience should also be equally regarded as our health care team’s understanding about our disease. As patients, we deserve support and encouragement from providers to help us in shared decision making.

Reminders for All of Us

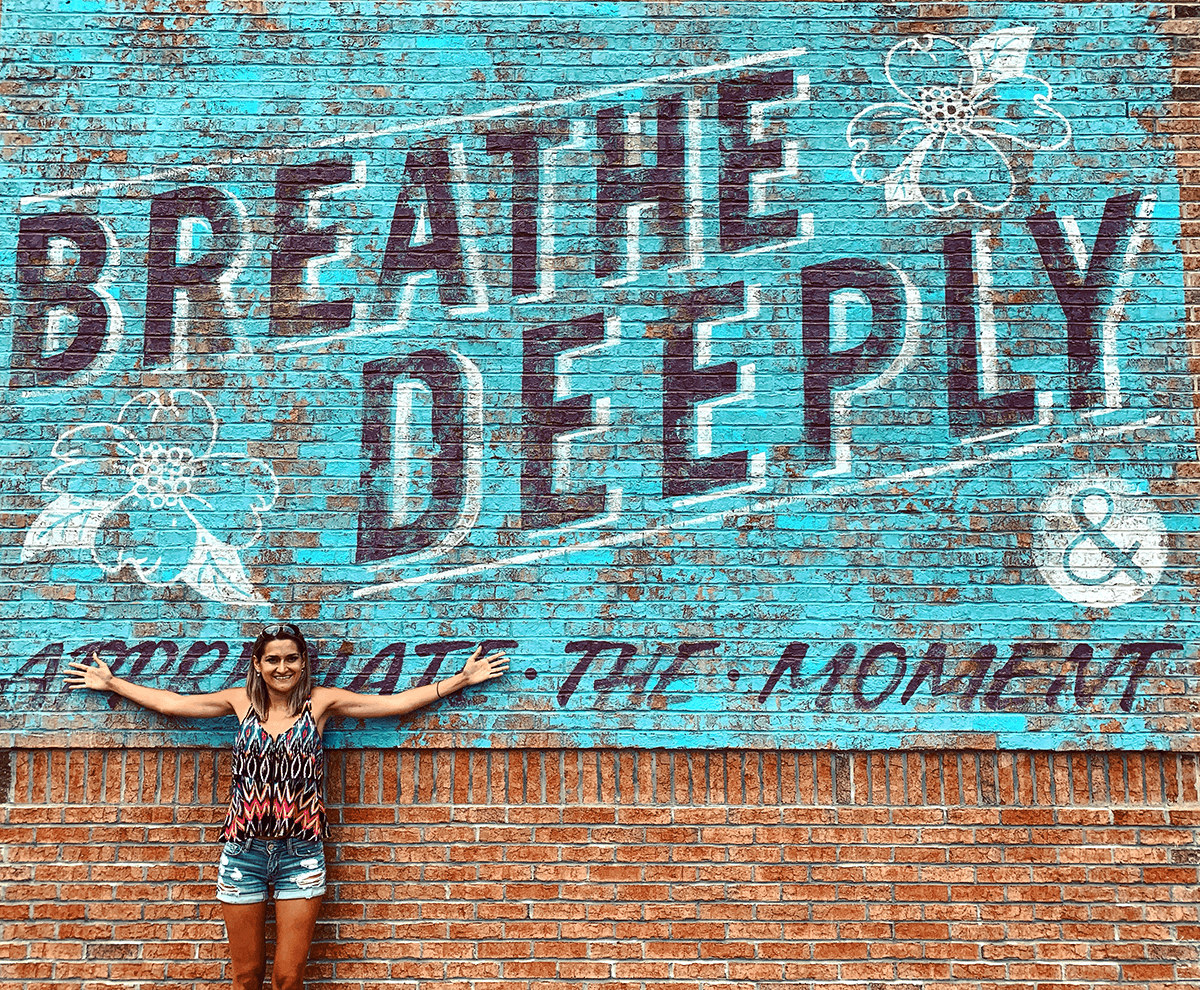

I hope this article serves as a reminder and as motivation for industry to serve the best interests of patients, for doctors to listen and build trust, and for us as patients to take the initiative with our own health care, to ask questions, and be inquisitive about clinical trial involvement and our treatment plans. We have the power to impact our health outcomes through the treatment decisions we make and the way we advocate for ourselves.

About the Author

Ella Balasa is a patient advocate, consultant, and a person living with cystic fibrosis. She has committed her time to empowering patients and advancing health care strategies. She speaks publicly about the value of patient perspective and has a passion for distilling clinical information for patient communities. Through opportunities working with health care organizations on content strategy, writing, speaking, clinical trial development, and sharing the patient experience, Ella aims to affect the health care landscape by raising awareness of rare diseases, promoting self-advocacy to patients, and providing valuable insights to organizations. More of her work and experiences can be found at www.EllaBalasa.com.